By Koaw 2023 -

BEST FEATURES FOR ID: (All of these features are discussed below in detail.)

Check if the cheek and the operculum are mostly scaled.

Check for a long snout (relative to the other pickerels.)

Compare the end of the maxilla vs. the position of the eye’s pupil.

Get a count on the submandibular pores.

Get a count on the branchiostegal rays.

Get a count on the lateral line scales.

Try the Quick Esox ID App that may offer a fast analysis, if needed.

Although color and patterning are very useful to assess when identifying the species within the genus Esox, features that are countable (meristic) and measurable (morphometric) are more reliable, and as such, are the focus of this guide. It’s important to examine more than one feature for confident IDs

Click to enlarge.

INTRO: Esox niger, or the chain pickerel (brochet maillé), is an esocid in the genus Esox, the pikes. [1] [2] Some anglers may still refer to this fish as “chainsides” [3], aptly describing the lateral chain-like patterning on the side of subadult and adult specimens.

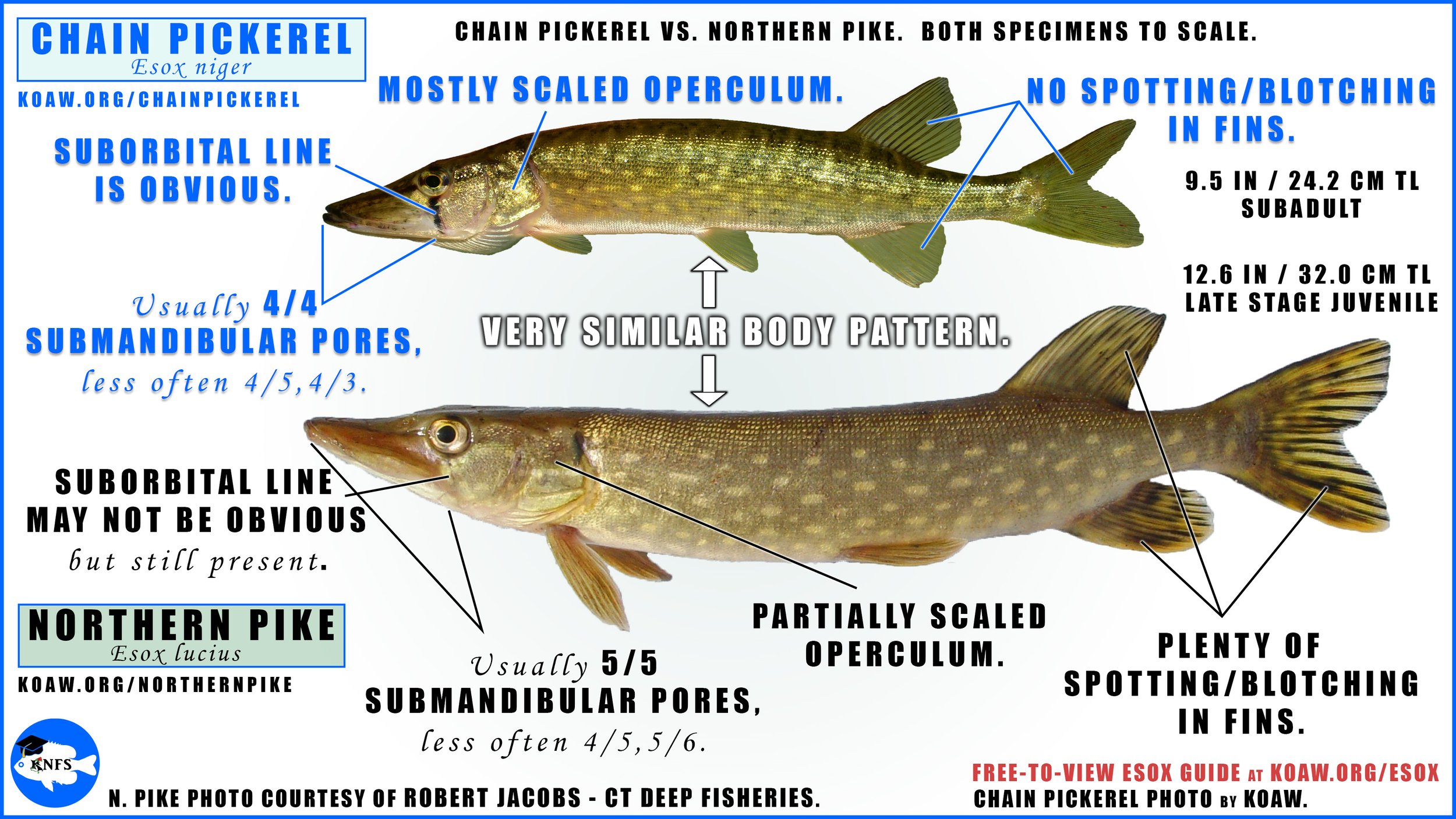

The chain pickerel (E. niger) is often mistaken for the grass and redfin pickerels (E. a. vermiculatus/E. a. americanus), especially young specimens, and with the northern pike (E. lucius), though the range overlap on the latter is much smaller. At times small gars may be mistaken for a chain pickerel. (See adjacent image to distinguish the chain pickerel vs. gars.)

KEY FEATURE #1 – SCALATION ON CHEEK & OPERCULUM: Of the North American esocids within Esox, only the chain pickerel (E. niger), the grass pickerel (E. a. vermiculatus), and redfin pickerel (E. a. americanus) will have a cheek & an operculum that are both fully scaled or nearly fully scaled.

These scales are best seen if the specimen’s head can be rotated underneath light, allowing for the shimmering scales to reveal themselves more easily. Aside from the youngest of juveniles, these scales should be readily visible.

If the cheek and operculum are mostly scaled, see Key Feature #2 to further help distinguish between the grass/redfin pickerels and the chain pickerel.

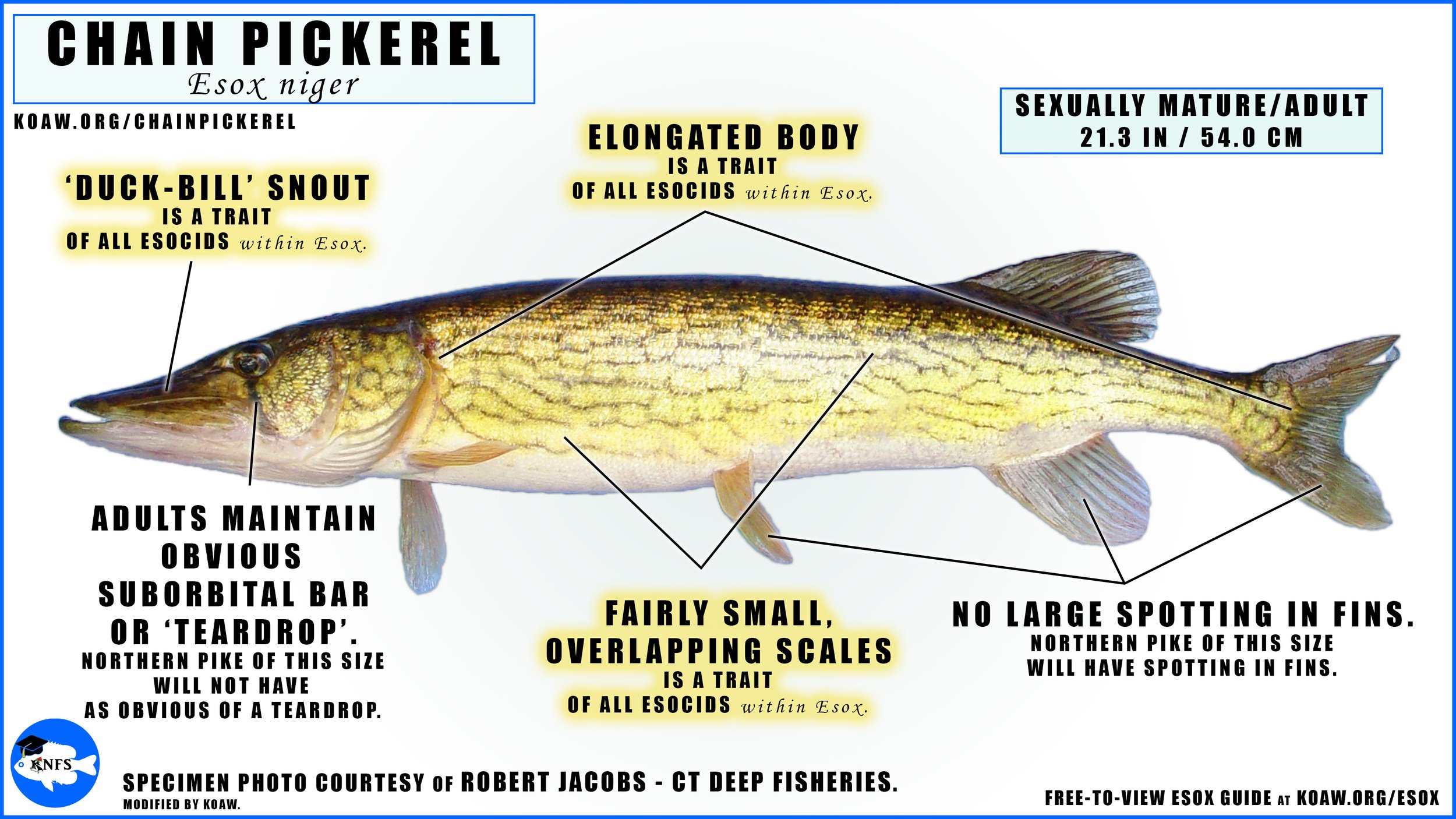

BODY: Like the other members of Esox, the body of the chain pickerel is very elongated with only a single dorsal fin that sits above an anal fin of similar size. The caudal fin is forked and the paired fins sit low on the body where the pelvic fins are fairly far back. The ‘duck-bill’ snout is characteristic of this genus where the mouth contains many sharp teeth.

The chain pickerel usually shows 16-19 anal rays, 20-21 dorsal rays, with 120-135 lateral line scales with a range of (114-138). Other meristic features are discussed on this page.

KEY FEATURE #2 – SNOUT LENGTH vs. POSTORBITAL LENGTH OF HEAD The chain pickerel has a snout length (SnL) that will usually exceed or be very near the postorbital length of the head (PToL), where SnL>PToL. The chain pickerel has the longest snout in this regard compared to the other members of Esox.

This feature best differentiates young chain pickerel from redfin pickerel. The redfin pickerel almost always has a snout length that will never exceed the postorbital length of the head.

Of the data collected for this guide, the snout length for chain pickerel fit into the postorbital length 0.94 times on average (=PToL/SnL) with a range of (0.78 – 1.13) including juvenile, subadult, adult specimens. A few specimens, both in the juvenile and adult categories had snout lengths that did not exceed the postorbital length of the head.

The redfin pickerel had a range of 1.15-1.53 for PToL/SnL where the smallest ratio for an adult specimen was 1.30.

Although the grass pickerel does, on average, have a shorter snout than the chain pickerel, there exists more overlap for this feature between the two fishes. The snout length for grass pickerel (SnL) fit into the postorbital length of the head (PtOL) for a mean of 1.17 times (PtOL/SnL) with a range of (0.95 – 1.33) including juvenile, subadult, and adult specimens. All specimens larger than 110 mm did not show a snout length greater than the postorbital length of the head, where a couple juvenile/subadult specimens showed only a slightly larger snout length than the postorbital length. [4]

The morphometrics measured for this guide were taken to verify the trends illuminated in Casselman et al. (1986) and Crossman (1966). [5] [6]

PATTERN/COLORATION: Adult and juvenile specimens express very different patterning. The chain-like patterning does not yet exist on juveniles, only becoming apparent during the transition into the subadult stage at around 8 in (20 cm), most obvious in the adult stage.

On adults, the chain-like pattern often continues onto the operculum and the cheek, but with smaller, more cylindrical yellowish spotting between the darker meshing. The lateral pattern on adults does vary and, at times, may more resemble the ‘jellybean’ like pattern on northern pike, hence why examining other features is important.

Mature chain pickerel maintain a distinct suborbital bar, or ‘teardrop’, that extends almost to the bottom of the head. The direction of slant of this teardrop changes as the fish matures: Juveniles often have a teardrop that slants towards the mouth while more mature specimens have a teardrop that often slants towards the rear of the fish. The other members of Esox will all express a suborbital bar—to some extent—during some or all phases of development. On the northern pike, this teardrop becomes much less conspicuous on specimens greater than ~12 in (30 cm) TL.

Although the ‘teardrop’ has been suggested as a good feature to examine for identification of the esocids in various guides [7] [8], there exists much variability between juveniles and adults of the same species, as well as much overlap between species. This guide, though recognizing the trends of suborbital bar presentation for each species, emphasizes that this feature should be regarded secondary in identification analyses. (I see misidentifications because IDs were based solely on the presence and/or slanting of a specimen’s teardrop.)

The fins of chain pickerel are mostly clear as juveniles, with rays that may express some scattered dark pigments. As the fish matures, the rays often develop more color from dusky to yellowish, while the interradial membranes tend not to develop much pigment in most populations. The caudal fin often expresses the darkest colors on the most proximal anterior/posterior margins and extending inwards. Note that the northern pike, aside from juveniles that have mostly transparent fins, will have very conspicuous irregular blotching in the fins, most apparent in the dorsal, anal, and caudal fins. Chain pickerel will not express such obvious blotching and patterning in the fins.

BLUE PICKEREL - Menzel & Green (1972) first described a curious phenotypic morph of the chain pickerel near Ithaca, New York in 1972; a small percentage of specimens within this population did not express the characteristic chain-like pattern of the species. Rather, the dorsal area of the fish was described as a metallic purplish-blue covered in darker spots that became blue and green along the sides. The suborbital bar, cheek, and operculum were described as purple. These “blue pickerel”, as the local anglers called them, only made up a small portion of the population; only 0.2% of collected chain pickerel specimens were ‘blue pickerel’ over a 6-year sampling period. [9] These ‘blue pickerel’ are not to be confused with ‘silver pike’, or the phenotypic morph seen in northern pike. The blue pickerel, for the most part, maintain similar morphometrics and meristics to ‘normal’ chain pickerel.

SEX DETERMINATION - After about attaining 8 in (20 cm) in length, the sex of a chain pickerel can be fairly well determined by examining the urogenital opening which is roughly twice as large as the anal opening on females and only slightly larger than the anal opening for males. [10] Males will have more of a slit compared to a roundly urogenital opening on females. However, this evaluation is not 100% reliable for sex determination. Only examining gonads and/or gamete extractions will provide absolute determination of sex. (The urogenital opening is closest to the anal fin while the anus is closer to the head; both openings will be right next to each other.)

KEY FEATURE #3 – MAXILLA VS. POSTION OF EYE’S PUPIL: On the chain pickerel, on both young and mature forms, the end of the maxilla will usually never extend as far as the anterior edge of the pupil, if even extending past the anterior margin of the eye. Keep mind to note that this guide refers to the maxilla and the supra-maxilla as the separate bones that they are. [11] The supra-maxilla on chain pickerel may pass the anterior edge of the pupil, but usually never passes the midpoint of the eye.

For mature redfin pickerel (E. a. americanus) the posterior end of the maxilla will almost always extend past the anterior edge of the pupil. Juvenile & subadult redfin pickerel will, in most cases, still at least have the maxilla extending past the anterior edge of the eye.

This feature is not as reliable to use for the comparison of chain pickerel vs. grass pickerel (E. a. vermiculatus) as the latter species tends to have less extension of the maxilla compared to redfin pickerel populations. For grass pickerel the posterior end of the maxilla does not usually pass the anterior portion of the pupil yet typically passes the anterior margin of the eye, though in some cases, still extending past the anterior margin of the pupil. [4] The morphometric data gathered for this ID guide agrees with the underlying trend of maxilla length presented in Crossman (1966) [6] .** A lateral line scale count and branchiostegal ray count is very helpful for chain pickerel vs. grass pickerel comparisons; (see below.)

SIZE: The chain pickerel is the intermediate-sized species of the North American esocids within the genus Esox, growing to be larger than both grass and redfin pickerels but reaching smaller sizes than the northern pike and the muskellunge.

In most populations, most adults will not exceed much past 24 in (60 cm). Page and Burr report the max TL of chain pickerel extends to 39 in (99 cm) probably based off a specimen taken in New Jersey 1904-1905, though this specimen is not recognized as a fishing-record in New Jersey. [7] [12] Many state angling records of chain pickerel are just below or just above 30 in (76 cm). The IGFA all-tackle world record is 9 lb 6 oz (4.25 kg). [13]

Any specimen larger than 22 in (56 cm) may be considered a very nice-sized catch and is probably at least 5-6 years old. [14]

Although first year chain pickerel are known to carry mature gametes, it’s more likely that successful spawning begins in the second year of life, [10] at sizes around 10 in (25 cm). In Virginia, Jenkins & Burkhead (1993) report most adult specimens are 13.5-20 in (35-50 cm) where large specimens are considered between 20-30 in (50-76 cm). [15]

KEY FEATURE #4 – SUBMANDIBULAR PORES: Counting the submandibular pores is a very beneficial ID feature on esocids. Typically, the chain pickerel will have a 4/4 count of pores on the underside of the jaw, or 4 pores on each side. These pores are very hard to see on juveniles and subadults, often a magnifying glass is required. These counts do vary, as some specimens may show counts such as 3/4 and 4/5; it is rare, but possible, to encounter a chain pickerel specimen with a count between 5/5 or 4/6.

The other pickerels, the grass and the redfin, also typically have a 4/4 count, similar to the chain pickerel. The northern pike, however, usually shows a count of 5/5 on most specimens, though variation does exist, where counts of 4/5 or 5/6 may occur. The muskellunge typically always has at least 6 pores a side. [5] [16] [6]

KEY FEATURE #5 – BRANCHIOSTEGAL RAYS: Counting the branchiostegal rays will really only be helpful in determining chain pickerel from the grass and redfin pickerels. Chain pickerel most often show 14-17 branchiostegal rays on a single side sometimes 12-13, while grass pickerel usually has 10-14, and the redfin pickerel has (10) 11-14, where counts of 15-16 may show up on these last two subspecies.

Since the northern pike usually has 13-16 branchiostegal rays, this feature is not helpful in distinguishing northern pike from the chain pickerel. The muskellunge, though hardly ever confused with the chain pickerel, typically shows 16-20 branchiostegal rays on a single side, more than the chain pickerel. [5] [6][16]

HABITAT: Chain pickerel may be found in a variety of habitat types. Like the other esocids, the chain pickerel is often associated with dense vegetation and calmer, quiet waters. [17] Sluggish rivers and creeks, lakes, ponds, channels, and wetlands all may hold chain pickerel. Chain pickerel may occur in moderately alkaline to very acidic water. [18] Occasionally found in brackish waters.

KEY FEATURE #6 – LATERAL LINE SCALES:

The lateral line scales may offer needed confidence on an ID between the chain pickerel and American pickerel. Chain pickerel typically show 120-135 lateral scales with a range of 114-138. The American pickerel (grass/redfin/intergrades) will typically have 110 or less lateral scales with a range of 92-117. Ergo, any pickerel showing more than 120 lateral line scales will most assuredly be a chain pickerel, or a possible hybrid.

The northern pike with 120-135 (105-148) lateral scales shares a lot of overlap with the chain pickerel for this feature and will usually not be of much benefit for differentiation. The muskellunge typically has more than 145 lateral scales. [5] [4]

Click to enlarge.

LOCATION: The northeastern most part of chain pickerel range now includes most all of Novia Scotia in Canada; in recent years the chain pickerel has done well to establish permanent populations in this region [19] and is suspected of having significant impacts on other fish populations. [20]

The native range begins in the southwestern parts of New Brunswick, continuing into Maine and down the Atlantic states. In Quebec, west of Montreal more near Sherbrooke, the range continues south into the Lake Champlain watershed including waters in New York and Vermont.

In recent years, chain pickerel are being found with more frequency in the northeastern waters of Lake Ontario, suggesting a range expansion in this region. [21] [22] Established populations exist south of Lake Ontario in New York. Scattered populations exist across Pennsylvania most abundant in the east of this state.

The USGS-NAS reports a good number of chain pickerel observations across Ohio and into Indiana, well outside the natural range, of which, is denoted by the differently shaded region on the adjacent map. [23] The first chain pickerel were stocked in Ohio in 1935 in Long Lake of Summit County of the Portage Lakes Chain. [24] This population has persisted and still exists within this watershed.

In the westernmost portion of Maryland, in Deep Creek Lake and the surrounding waters, a healthy population of chain pickerel exists after human introductions. The remaining populations in Maryland are only found in the far eastern portions of the state.

The range continues south, mostly east of the Appalachian Mountains and into Florida. Scattered populations exist in Georgia, Alabama, and to a lesser extent, in Mississippi. The Mississippi River Basin does have healthy chain pickerel populations, though not often encountered near the actual Mississippi River. Populations are found in the southeastern parts of Missouri and possibly populations still exist in the southern parts of Illinois and into Kentucky. Louisiana, the eastern most parts of Texas, and Arkansas contain chain pickerel. The very eastern parts of Tennessee, at least, contain chain pickerel.

In Texas, near Kerrville, once stocked populations may still persist (not included on map.)

FISHING: Unlike the smaller pickerels, the chain pickerel is commonly targeted by anglers. The meat is tasty and large specimens put up a good fight, especially on light gear.

The chain pickerel is an opportunistic feeder; many bait options will do well. Spoons, crankbaits, and live minnows are popular choices. My lure-of-choice for chain pickerel is a safety-pin spinnerbait if targeting pickerel sitting in the shallows. Safety-pin spinnerbaits are mostly weedless and produced a lot of flash and thump—reaction strikes are easy to come by.

Click to enlarge.

If the shallows are too warm, and the pickerel moved a bit deeper, I prefer tossing a crankbait that’ll target a specific depth that’ll be just above the weeds; more than likely chain pickerel will still want to be sitting in or near cover even at depth. Rapala’s DT-6 & DT-10 are my go-to lure when targeting these moderate depths.

Chain pickerel have very sharp teeth. If targeting big specimens, use a strong line or even a steel leader to prevent avoidable line cuts.

**NOTE from KEY FEATURE #3 This feature is suggested as a distinguishable trait in Crossman (1966) and Casselman et al. (1986). Yet, it seems that within these aforementioned sources the supra-maxilla bone may be used synonymously with the maxilla bone. Though, even if the posterior end of supra-maxilla is used rather than the maxilla, the position of supra-maxilla on chain pickerel still does not usually extend to the midpoint of the pupil and in the redfin pickerel this bone only extends farther past the midpoint of the eye. [6] [5] The morphometric data I collected is used to influence my graphics and descriptions on this trend.

REFERENCES:

[1] C. A. Lesueur, "Description of several new species of the genus Esox of North America," Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences., vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 413-417, 1818.

[2] R. Fricke, W. N. Eschmeyer and R. van der Laan, "ESCHMEYER'S CATALOG OF FISHES: GENERA, SPECIES, REFERENCES". http://researcharchive.calacademy.org/research/ichthyology/catalog/fishcatmain.asp

[3] A.J. McLane, McClane's New Standard Fishing Encyclopedia, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974.

[4] Koaw, "Select Morphometrics and Meristics of Esocids," Koaw Nature - KNFS, 2023. http://www.koaw/org/esoxdatakoaw

[5] J. M. Casselman, E. J. Crossman, P. E. Ihssen, J. D. Reist and H. E. Booke, "Identification of Muskellunge, Northern Pike, and their Hybrids," Am. Fish. Soc. Spec. Publ., vol. 15, pp. 14-46, 1986.

[6] E. J. Crossman, "A Taxonomic Study of Esox americanus and Its Subspecies in Eastern North America," Copeia, vol. 1, pp. 1-20, 1966. [7] L. M. Page and B. M. Burr, Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of North America North of Mexico, NY: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011. [8] C. L. Hubbs, K. F. Lagler and G. R. Smith, Fishes of the Great Lakes Region: Revised Edition, University of Michigan Press, 2004.

[9] B. W. Menzel and D. M. Green Jr., "A Color Mutant of the Chain Pickerel, Esox niger LeSueur," Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, vol. 101, no. 2, pp. 370-372, 1972.

[10] G. E. Lewis, "Observations of the Chain Pickerel in West Virginia," West Virginia Dept. of Nat. Res., vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 33-37, 1974.

[11] R. Brocklehurst, L. Porro, A. Herrel, D. Adriaens and E. Rayfield, "A digital dissection of two teleost fishes: comparative functional anatomy of the cranial musculoskeletal system in pike (Esox lucius) and eel (Anguilla anguilla)," Journal of Anatomy, vol. 235, pp. 189-204, 2019.

[12] NJ FIsh & Wildlife, "New Jersey State Record Freshwater Sport Fish," NJ Dept. of Env. Protection, 2022. https://dep.nj.gov/njfw/fishing/freshwater/new-jersey-state-record-freshwater-sport-fish/

[13] IGFA - The International Game Fish Association, "Esox niger - Chain Pickerel World-Record," IGFA, 2022. https://igfa.org/igfa-world-records-search/?search_type=CommonName&search_term_1=Pickerel,%20chain

[14] F. Grice, "Elasticity of Growth of Yellow Perch, Chain Pickerel, and Largemouth Bass in Some Reclaimed Massachussetts Waters," Trans. of the Amer. Fish. Soc., vol. 88, no. 4, pp. 332-335, 2011.

[15] R. E. Jenkins and N. M. Burkhead, Freshwater Fishes of Virginia, Bethesda, MD: American Fisheries Society, 1993.

[16] S. Eddy, "Hybridization between Northern Pike (Esox lucius) and Muskellunge (Esox masquinongy)," Jour. of the Minn. Acad. of Sci., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 38-43, 1944.

[17] R. P. Jacobs and E. B. O'Donnell, Freshwater Fishes of Connecticut; A Pictorial Guide to, Hartford: Connecticut Dept. of Env. Protection, 2009.

[18] E. J. Crossman and W. B. Scott, Freshwater Fishes of Canada, vol. Bul. 184, Ottawa: Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 1973.

[19] iNaturalist.org, "Esox niger - Chain Pickerel," iNaturalist Cal. Acad. of Sci. Nat Geo., 2022.

[20] S. C. Mitchell, J. E. LeBlanc and A. J. Heggelin, "Impact of Introduced Chain Pickerel (Esox niger) on Lake Fish Communities in Nova Scotia, Canada," St. Frances Xavier Univ/Nova Scotia Dept. of Fish. and Aqua..

[21] J. A. Hoyle and C. Lake, "First Occurrence of Chain Pickerel (Esox niger) in Ontario: Possible Range Expansion from New York Waters of Eastern Lake Ontario," Canadian Field-Naturalist, vol. 125, no. 1, pp. 16-21, 2011.

[22] B. P. Morrison and D. J. Moore, "First Occurrence of a Juvenile Chain Pickerel (Esox niger) in Ontario Waters of Lake Ontario," Canadian Field-Naturalist, vol. 131, no. 4, pp. 331-334, 2017.

[23] NAS-USGS, "Esox niger - Chain Pickerel Point Map," USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species, 2022. https://nas.er.usgs.gov/viewer/omap.aspx?SpeciesID=681

[24] D. C. Armbruster, "OBSERVATIONS ON THE NATURAL HISTORY OF THE CHAIN PICKEREL (ESOX NIGER)," The Ohio Journal of Science, vol. 59, no. 1, 1959.