By Koaw - November, 2020 (Updated 2022)

GENERAL: The bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus – Rafinesque, 1819) is the most ubiquitous of all the lepomid sunfishes here in North America, existing in all the contiguous states within the United States. This is a fascinating species with seasonal morphological changes, complex mating habits and the boldness of character to be not just a successful species in native and introduced ranges but also to be quite an intriguing fish.

The colors and patterns may present a wide array of phenotypic expressions as specimens mature, between sexes, as well as the variance that exists within different habitat types. (Notes on subspecies below.) The dark opercular flap, the blue coloring along the bottom of the chin/cheek/operculum and the spot at the second dorsal fin are ideal features for an ID. Breeding males that have built a nest will have a bulge on their head above the eye that extends along the nape, a very red/orange breast and darker fins.

BODY: The bluegill has a strongly compressed, deep body like a disc. The lateral line is complete with 38-48 lateral scales. [1] Typically there are 10 dorsal spines, 11-12 dorsal rays, 3 anal spines, 11 (10) anal soft rays and 13 (12,14) pectoral rays. [2] [1]

SEXING BLUEGILL: The bluegill engages in very interesting forms of sexual selection where certain males may be satellites, males taking on the appearance of a female to gain access to a nest, or sneakers, smaller males that wait for an opportunity to fertilize eggs in the nest while the other parental male is distracted, likely by a female or other sneakers/satellites. The parental males build and fiercely guard nests to court females. [3] A parental male engages in elaborate courtship rituals. One ritual involves the male wooing a female with audible grunts, all the while rushing at her and then back to the nest in a repeated fashion. [4] If successful in attracting a female to the nest, he will swim circles around her, keeping her within the limits of the nest and further enticing her to lay her eggs. (I have watched many hours of footage of lepomids going about these rituals, and I must say, it is remarkable witnessing the effort and devotion that parental males put into building the nests, courting the females, and defending the nest as well as the aerating and cleaning of the fertilized eggs.)

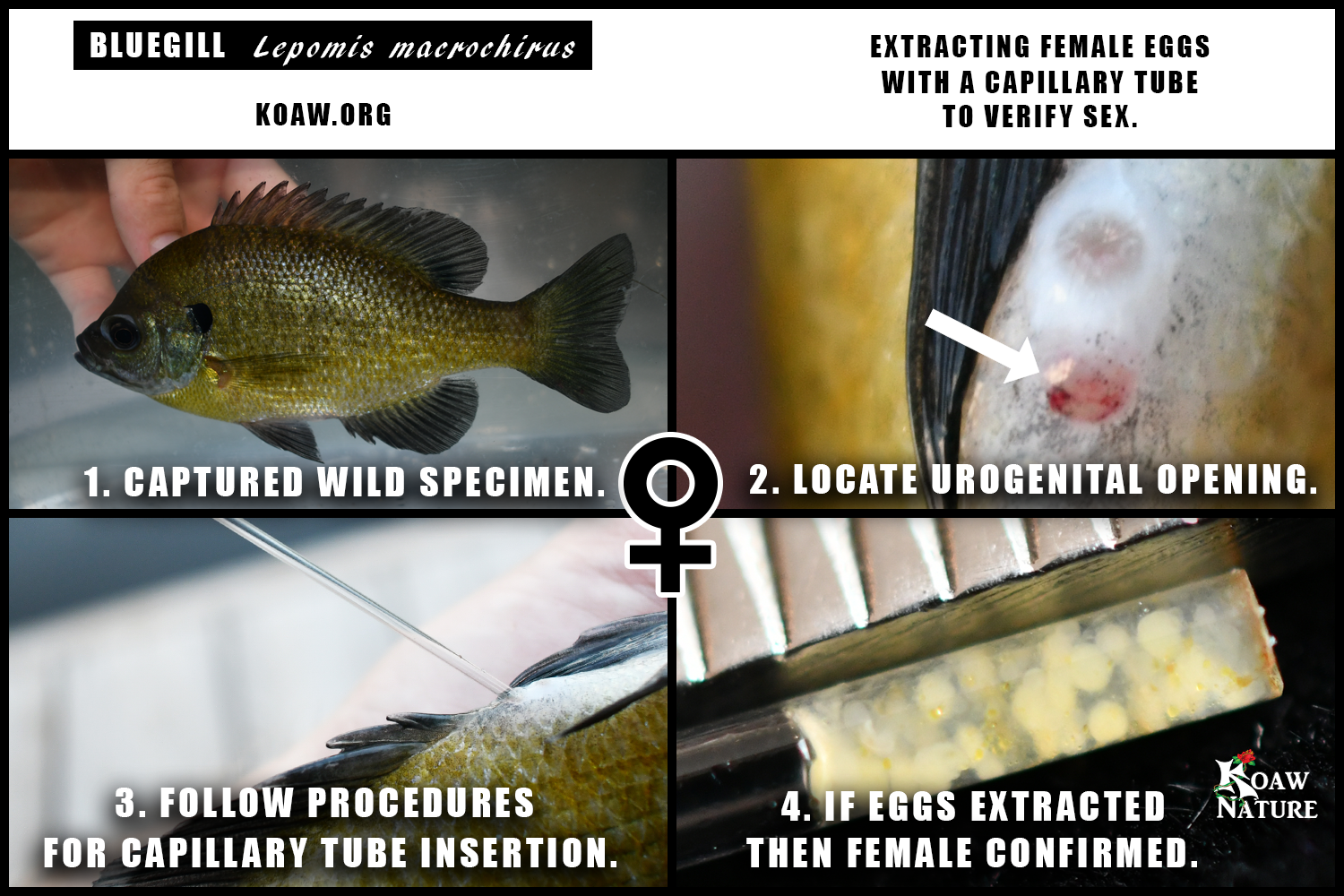

With the existence of these sneakers and satellites, often it can be difficult to assess the sex of a specimen. Often an examination of the gonads or confirmation of gametes (sperm/eggs) is required for a confident ID, especially for immature specimens. Other methods of determining sex exist without needing to kill the fish such as performing a biopsy of the gonads or inserting capillary tubes into the urogenital opening to extract gametes, although not all specimens will survive an invasive procedure. I was able to confidently ID both specimens in the summary image above by gently rubbing the abdomen of the male to see the milky-colored seminal fluid or milt and the large swollen, pink fleshy condition of the female’s urogenital opening was sufficient for determining the sex.

In one of the images below, you’ll see how I followed the procedures by Mischke et al. to extract eggs from a female to confirm an identification. Using a 1.1 to 1.2 mm inner diameter capillary tube (with 0.2 mm to ±0.02 mm walls, of which, I am yet to see if are too large for specimens under ~13 cm TL), the tube was gently inserted into the urogenital opening while attempting to slightly angle it towards the tail and one side. Still with a gentle force, the tube was furthered through the oviduct and into the ovary where, again using gentle force, a back-and-forth twirling of the capillary tube was used. With the tube still inserted, a finger was placed on the open end of the tube to create suction followed by a slow removal of the tube. Eggs present in the capillary tube confirmed a female identification. [5]

Another possible non-invasive method for sexing bluegills is simply by examining the condition and size of the urogenital canal.

T. McComish wrote in the Progressive Fish-Culturist of two studies that had a reliable method for sexual differentiation based on exterior examination of the urogenital canal (though I can’t seem to track down the studies he referenced.) The males either have a very small fleshy area or no visible fleshy area around the urogenital opening with no ring-like appearance. Males will often have a wedge-shaped opening. The females have a roundly, pink and fleshy opening that resembles a “small, swollen, doughnutlike ring” where this area is more swollen during breeding seasons. This method is reported only reliable on specimens around 7.5-10 cm or greater in total length. [6]

J. Brauhn reported difficulty determining the sex of sub-adults and non-spawning adults using the aforementioned technique. He was only able to separate males of 9 months (5 cm TL) with 80% accuracy but males of 12 months (10 cm TL) were separated with 99% accuracy. He suggests examining (4) other traits in addition to the urogenital opening to provide more confidence in sexual differentiation: The operculum, gular area, body and dorsal fin.

Operculum: Males will have an opercular lobe (of which I assume he is referring to the opercular flap or ear flap) that is more square and heavily pigmented while females have a more roundly lobe with less pigmentation.

Gular area: Males will have pigmentation of black while females have pigmentation of yellow.

Body: Males will have a darker cast whiles females have a lighter cast.

Dorsal fin: Males have a pronounced spot at base of 2d dorsal fin while females have a less distinct spot. [7]

COLORATION: The upper body will generally have a dark olive appearance with green and yellow flecks. Often bluegill have lateral bars that are more pronounced and chainlike on juveniles and sub-adults. Bars along the side are fainter on adults and may not be visible during the breeding season, especially as males change appearance, and possibly absent in turbid waters. [1] Juveniles will have a gray/brown appearance dorsally and a steely blue on the sides. [8]

A pair of blue lines will streak along the chin, into the lower cheek and into the operculum where this is more apparent on mature specimens and breeding males. Most all specimens will have a dark blotch at the posterior base of the 2d dorsal fin.

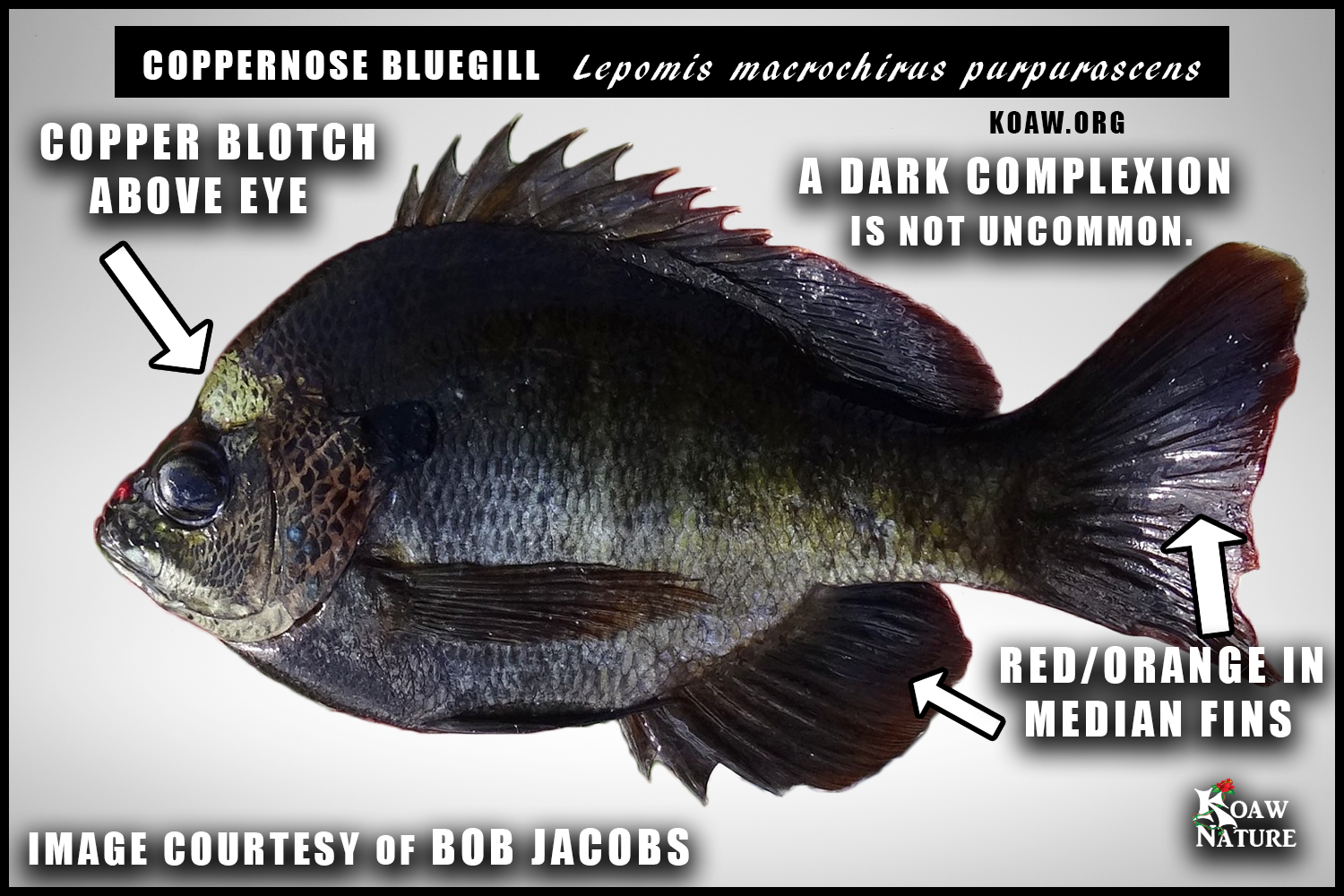

NOTES ON SUBSPECIES: There are suggested subspecies of the bluegill, yet a great amount of uncertainty exists as to how many and their nomenclature. The coppernose bluegill, or Florida bluegill, (Lepomis macrochirus purpurascens), of which, is southeastern in its distribution in the United States, primarily in Florida and southern Georgia. [9] [10] This subspecies is often stocked in the southeastern states. Besides the adjacent photo, I also included an image to the carousal images under GENERAL/BODY (above). There remains ambiguity regarding the nomenclature of this subspecies as it is suggested this subspecies should be named after Cope’s description of the Florida Bluegill in 1877, Lepomis mystacalis, [11] due to the original errors in describing a far-too-northern type locality under the nominal L. m. purpurascens.

The coppernose bluegill’s distinct features include a copper-colored blotch above the eye that often connects to a similarly colored-blotch above the opercular flap, more red and orange in the median fins than a typical bluegill as well as pale margins on the median fins, sometimes orange, red or pink. A darker purplish color is common, especially in breeding males. [12] Often this subspecies has a ‘wild’ array of colors and often presents an anal fin blotch similar to that of a green sunfish. The young have been described to differ from the northern subspecies by having thicker, more even bars and higher fin spines as well as the red in the median fins that fades with age. [12]

Another subspecies is mentioned faintly in literature by Hubbs & Lagler, L. m. specious, [10] and is located in the southwest; though this subspecies has not been shown to have distinct genetic differences from Lepomis macrochirus macrochirus, and has not been accepted as a valid subspecies by any authorities on the genus.[11]

The northern bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus macrochirus) is the ubiquitous nominal subspecies native to most of the eastern half of the United States, now introduced widely across North America. I have refrained, in part, from explicitly labeling many subspecies as L. m. macrochirus as I do not feel adequate resolution and evidence has been supplied regarding these subspecies and their distinctions. Previous ichthyologists have desired to place the coppernose bluegill as a separate species; though Avise and Smith (1972) present a rational, mostly genetic-based argument as to why the coppernose bluegill should remain with a conspecific description. [9] Though more current authors still argue that more genetic and morphological data should be analyzed to determine if the coppernose/Florida bluegill should be regarded as a distinct species. [11] I would agree, especially after the splitting of the spotted sunfish (Lepomis punctatus) and redspotted sunfish (Lepomis miniatus); this topic should be re-evaluated especially as the morphological differences are so distinct between the coppernose/Florida bluegill and the northern bluegill.

SIZE: To 41 cm (16.25 in); [1] this extreme size range listed by Page & Burr is not a commonality as most wild specimens will usually not exceed 30 cm (12 in). IGFA All-Tackle Record: 2.15 kg (4 lb 12 oz). [13]

OPERCULAR FLAP: The bluegill is relatively simple to ID just by examining the “ear flap” on the posterior end of the gill plate. The bluegill is the only species within Lepomis to have an all dark ear flap with dark edging as an adult, of which, may include a dark blue edging; all other mature sunfishes within the genus have at least some color (yellow, red, orange, white, or light blue) around and/or on the opercular flap.

Keep in mind there may be a little bit of color (typically white) on the very anterior edges as is seen in the adjacent image.

The spotted sunfish (Lepomis punctatus) does not have too much color around the opercular flap but will most often express at least a bluish/white on the anterior ventral edge. The spotted sunfish’s color on this edge extends farther than the minuscule color expressed on a bluegill’s anterior edge. Likewise, the bantam sunfish (Lepomis symmetricus) may not always have conspicuous color around the ear flap, especially on the small specimens

GILL RAKERS: The gill rakers on the 1st gill arch are long and thin. These can be examined by gently lifting the gill plate and looking at the white portion above the red filaments on the gill arch closest to the gill plate.

I made a video describing how to locate and find these rakers that is hosted on Koaw Nature’s Fishing Smarts YouTube channel.

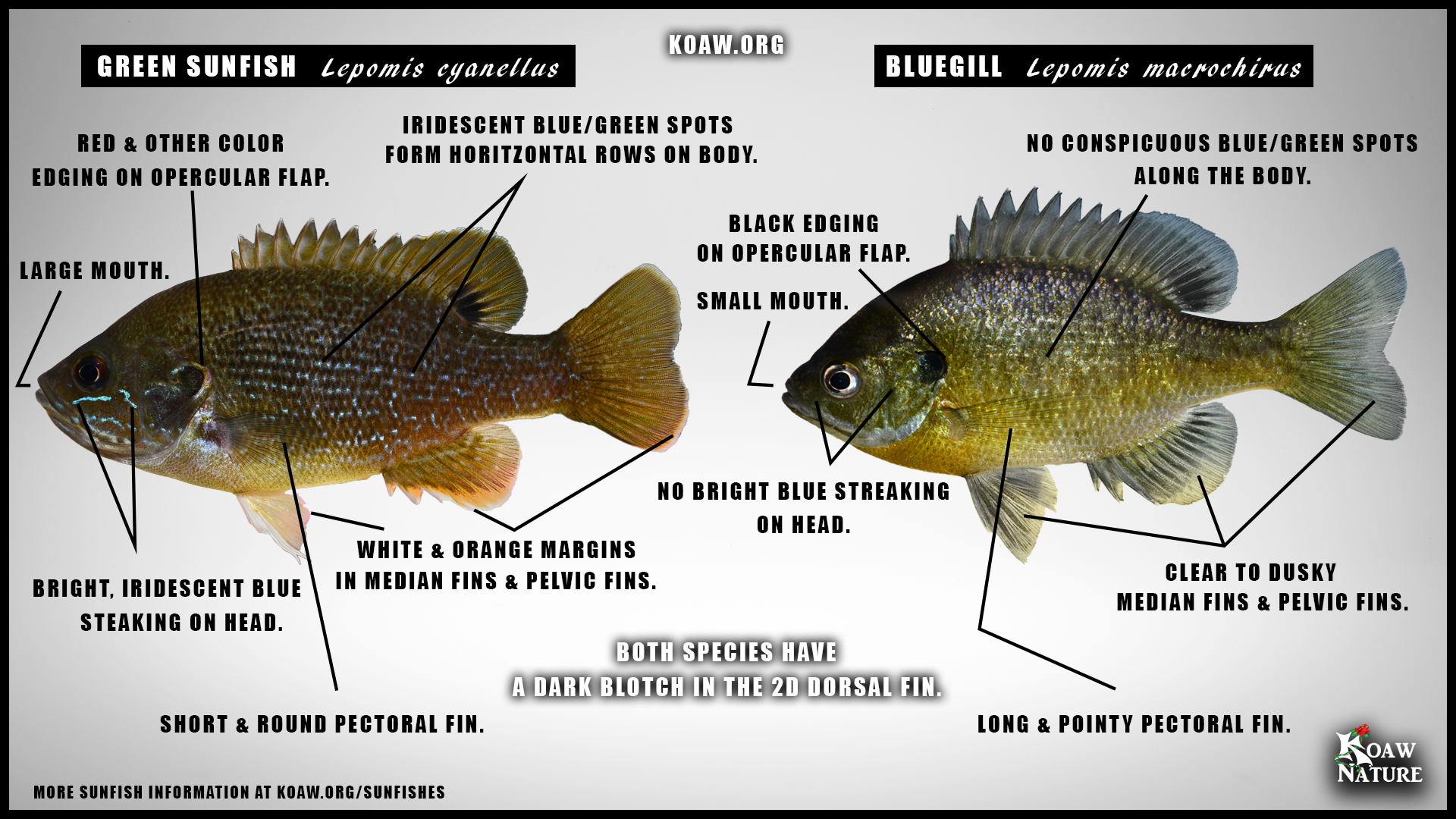

MOUTH SIZE: The bluegill mouth is relatively small compared to certain other sunfishes, such as the green sunfish (Lepomis cyanellus). The upper jaw does not extend under the pupil and often aligns with the anterior edge of the eye.

More specifically, the maxilla’s most posterior edge will not exceed the anterior edge of the pupil (as the fish’s mouth is closed or nearly closed.)

The mouth in the second photo is of a large breeding male, showing the normal maximum posterior extension that still does not extend under the eye’s pupil.

PECTORAL FIN: The pectoral fins (one on each lateral side) are long and pointed, usually reaching past the eye if bent forward. Often with 13 pectoral rays. [1][2] The pectoral fin may be shorter on juveniles, not quite passing the eye.

This a great feature to utilize for distinguishing against other species. Only the pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus) and the redear sunfish (Lepomis microlophus) also have long, pointy pectoral fins.

HABITAT: Bluegills are successful in many different aquatic environments such as rivers, creeks, lakes, swamps and various impoundments. The bluegill is typically more successful in areas with moderate amounts of vegetation but also able to survive in a wide variety of conditions. [8] Males will build nests in the calmer shallows during breeding seasons within sandy or rocky bottoms and sometimes in benthic detritus.

Bluegills will stack around structure like vegetation, sunken shelters, fallen trees and floating docks or boats. In creeks and rivers, find bluegill in calmer waters and pools. This fish may swim alone though tends to exhibit shoaling behavior (the swim together in groups of two or more).

CLICK TO ENLARGE - This distribution map is an illustrated approximation created by Koaw primarily pulling data and information from USGS-NAS, Research Grade observations from iNaturalist and Page & Burr’s Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes.

LOCATION: The bluegill is native to the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin, Mississippi River Basin, Atlantic and Gulf drainages, including the Cape Fear River Basin and Rio Grande River Basin, including parts of Northern Mexico. [1] [14]

This species has been widely introduced across the United States and in parts of Canada and Mexico. Other countries like Korea, Japan and South Africa also have well established populations of introduced bluegill. [14] [15]

Lepomis macrochirus purpurascens (coppernose bluegill) is a recognized subspecies that is most genetically diverse from other bluegill in peninsular Florida and southeast Georgia. [9] This subspecies is often stocked in the southeastern states and is also present in North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama and even as far west as Texas.

FISHING: A bluegill will take just about anything that fits in its mouth—seriously! I’ve had bluegill nibble on the moles on my back while swimming (yes, bleeding can occur) as well as nipping on my toes when sitting on the edge of a dock. But don’t worry—the teeth of bluegill are not that sharp and the gentle biting is more ticklish than painful.

Live bait like worms, leeches and cut-baits like shrimp will always work. Fishing with flies for bluegill is a lot of excitement. A fly rod isn’t even necessary! Just grab a light spinning pole with light line (2-6 lb) and you’ll enjoy the action. Big breeding males put up enjoyable fights.

Small spinnerbaits and soft plastics will also do the trick. Really…it’s hard not to catch a bluegill even when a bluegill isn’t the species desired!

SIMILAR SPECIES: I often see fishers mistake redbreast sunfish (Lepomis auritus) for bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus) males in breeding colors. The parental male bluegill takes on a very red to orange breast during the breeding season that looks very similar to a redbreast’s breast. Check out the graphic I created that should clear the water on this one.

The green sunfish and bluegill are not often confused with one another, but it does happen. This side-by-side comparison is actually a great reference for new sunfish identifiers because it shows much of the range of all lepomid species for many characteristics.

REFERENCES:

L. M. Page and B. M. Burr, Peterson Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2011.

N. K. Thakur, M. Takahashi and S. Murachi, "Osteology of Bluegill Sunfish, Lepomis macrochirus RAFINESQUE," J. Fac. Fish. Anim. Husb., vol. 1971, no. 10, pp. 73-101, 1971.

M. R. Gross, "Sneakers, satellites, and parentals: polymorphic mating strategies in North American sunfishes.," Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie, vol. 60, pp. 1-26, 1982.

J. W. Gerald, "Sound Production During Courtship in Six Species of Sunfish (Centrarchidae)," Evolution, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 75-87, 1971.

C. C. Mischke, J. E. Morris and R. L. Lane, "Species Profile: Hybrid Sunfish," Southern Regional Aquaculture Center ; SRAC Publication No. 7205, 2007.

T. S. McComish, "Sexual Differentiation of Bluegills by the Urogenital Opening," The Progressive Fish-Culturist, vol. 30, no. 1, p. 28, 1968.

J. L. Brauhn, "A Suggested Method for Sexing Bluegills," The Progressive Fish-Culturist, vol. 34, no. 1, p. 17, 1972.

R. P. Jacobs and E. B. O'Donnell, "Sunfishes and Freshwater Basses," in Freshwater Fishes of Connecticut, Hartford, Connecticut Dept. of Environmental Protection, 2009, pp. 164-180.

J. C. Avise and M. H. Smith, "Biochemical Genetics of Sunfish I. Geographic Variation and Subspecific Intergradation in the Bluegill, Lepomis macrochirus," Evolution, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 42-56, 1974.

C. L. Hubbs and K. F. Lagler, FISHES of the Great Lakes Region: Revised Edition/ Revised by Gerald R. Smith, The University of Michigan Press, 2004.

T. J. Near and J. B. Koppelman, "Species diversity, phylogeny and phylogeography of Centrarchidae," in Centrarchid Fishes: Diversity, Biology, and Conservation, S. J. Cooke and D. P. Philipp, Eds., Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, pp. 4-5.

C. L. Hubbs and R. E. Allen, "FISHES OF SILVER SPRINGS, FLORIDA," Proceedings of the Florida Academy of Sciences, vol. 6, no. 3/4, pp. 110-130, 1943.

IGFA, "BLUEGILL IGFA All-Tackle World Record,"2020. [Online]. Available: https://igfa.org/igfa-world-records-search/?search_type=CommonName&search_term_1=Bluegill.

USGS, "USGS-NAS Lepomis macrochirus," [Online]. Available: https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?SpeciesID=385. [Accessed 2020 August].

iNaturalist, "Lepomis macrochirus Bluegill,"iNaturalist, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.inaturalist.org/taxa/49591-Lepomis-macrochirus. [Accessed August 2020].

M. L. Warren, Jr., "Centrarchid Identification and Natural History," in Centrarchid Fishes: Diversity, Biology, and Conservation, S. J. Cooke and D. P. Philipp, Eds., Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, pp. 413-418.

D. S. Lee, C. R. Gilbert, C. H. Hocutt, R. E. Jenkins, D. E. McAllister and J. J. R. Stauffer, Atlas of North American Freshwater Fishes, Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State Museum of Natural History, 1980.